It is not every day that we have the opportunity to use our experience in traditional plastering techniques on something as large and spectacular as the project of casting a giant heart for the sculptor Veronika Durova. We were approached to see if we would cast a model of a concrete heart in thin-walled concrete, and only in a plaster mould that would be destroyed when it was moulded. So one try! You can imagine that this was extremely stressful as any mistake could have led to the destruction of the precious model and the loss of everything the sculptor had spent considerable time on. This was a really exciting challenge!

Veronika Durová has been working on the model of the giant heart for 6 years, basically from time and now it is time to cast it. Taking into account the giant dimensions and therefore the possible weight, it was decided that the heart would be cast in high strength thin-walled fibreglass and would therefore be hollow. We also flirted with the idea of pouring it in foam concrete, but the weight would still be enormous and we would not have such a solid outer surface. The foam concrete outer layer could suffer from shipping or icing and would reveal its "bubbly" nature. We needed something lightweight but very strong on the outside. Something that would hold itself up, be able to be transported without the surface suffering in any way and have the ability to be anchored securely in the public space. Hence the thoroughly interlocking hollow casting here.

Gypsum mould

Even though the model was made of plaster, we used the technique of blind mould, the so-called "blind". It is a way of forming the first model, in which the model itself is destroyed. Often the model is made of sculptural clay. It is cast in plaster with a minimum number of dividing planes and after it has set, the clay is removed from the mould. The gypsum 'caddy' is then thoroughly separated (e.g. with soap dissolved in water) and reassembled to form the plaster model. It is then easier to work out the details and is also more helpful in making a mould for the final casting, whatever the material.

In this case, it was necessary to preserve all the capillaries and the biological structure of the surface of the heart in plaster, which is not very flexible. Thus, the parts were gradually shaped so that they could be removed. Work cleverly with the division, but at the same time, don't be completely afraid. If the mould is divided too much, it would be very difficult to assemble, and each successive joint could cause some inaccuracy that would lead to deformation or even the impossibility of assembling the mould. However, the mould was able to be assembled perfectly and accurately, preserving even the smallest details of the biological texture without major complications. The assembled mould was substantially reinforced with plaster dressing and wooden structure. The whole thing was then thoroughly separated multiple times with shellac and beeswax. It's kind of a dream come true when you can go into a one-piece mould, correct any inaccuracies and get a perfect seamless casting. Not every mould can be entered like this and corrected as needed. It was a bit like the French series "once upon a time".

We built the mould with the base up to avoid having to apply the concrete mix to the direct ceiling, as we would have had to do if it had been left lying down. This leaves us with "only" the overhang, where the model tapers to the base, as the most difficult part. The inverted and fixed mould was waxed one last time and the surface was thoroughly sanded.

Concrete mixture

When pouring concrete, we often work with plasticizers to make the concrete flow, so that it can flow into the most inaccessible parts of the mould and compact it sufficiently by displacing air bubbles. In this case, we wanted the concrete to do the opposite. We needed the concrete not to flow and instead to stick to the slippery waxed and polished surface and still in the overhang.

To achieve this, we mixed the concrete mix using, among other things, the thixotropic component Densocrete PPE TH from Betosan. This ingredient is essentially the opposite of a plasticiser and ensures that the concrete behaves like a thixotropic liquid. As long as we work with it, it is ductile and plastic. But once we stop kneading it, it stops behaving ductile and sticks in place. Combined with a balanced ratio of glass fibre, micro-ground silica fume and pyrogenic silica, we have developed a mix with the necessary properties and sufficient strength.

Casting

This way, we were able to get into the mould and carefully brush the heart with the first fine layer with a smaller proportion of aggregate so as to bring out the details on the mould, but at the same time not scratch the polished wax surface.

This was followed by a layer with additional glass mats to thoroughly prime. Several layers were created and before the final one, we started to implement specially modified iron steel bars (roxors) into the model. These were forged into the surface on one side, bent and clouded. Our idea was that if pressure was applied from the inside, they would have the ability to spread the pressure and apply more surface area to the concrete inner wall of the heart itself. The internal iron structure was to be welded onto the final structure to be mounted on a stud for placement in a public space. We also took care Thanks to a tried and tested mix and perfect preparation, we managed to cast the whole heart without any major problems and all that was left to do was to keep an eye on a calm and well-hydrated maturation.

Removal of the mould

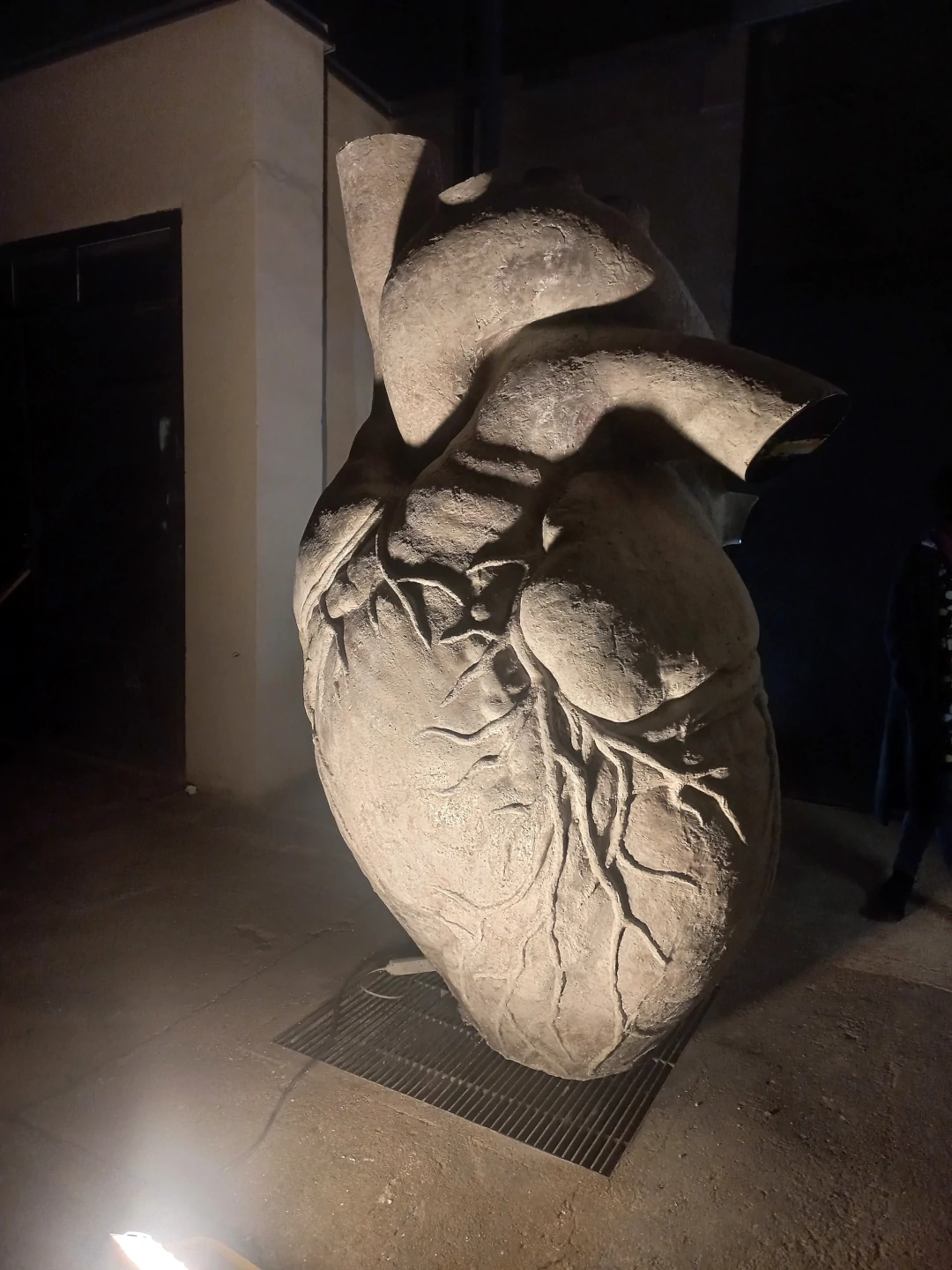

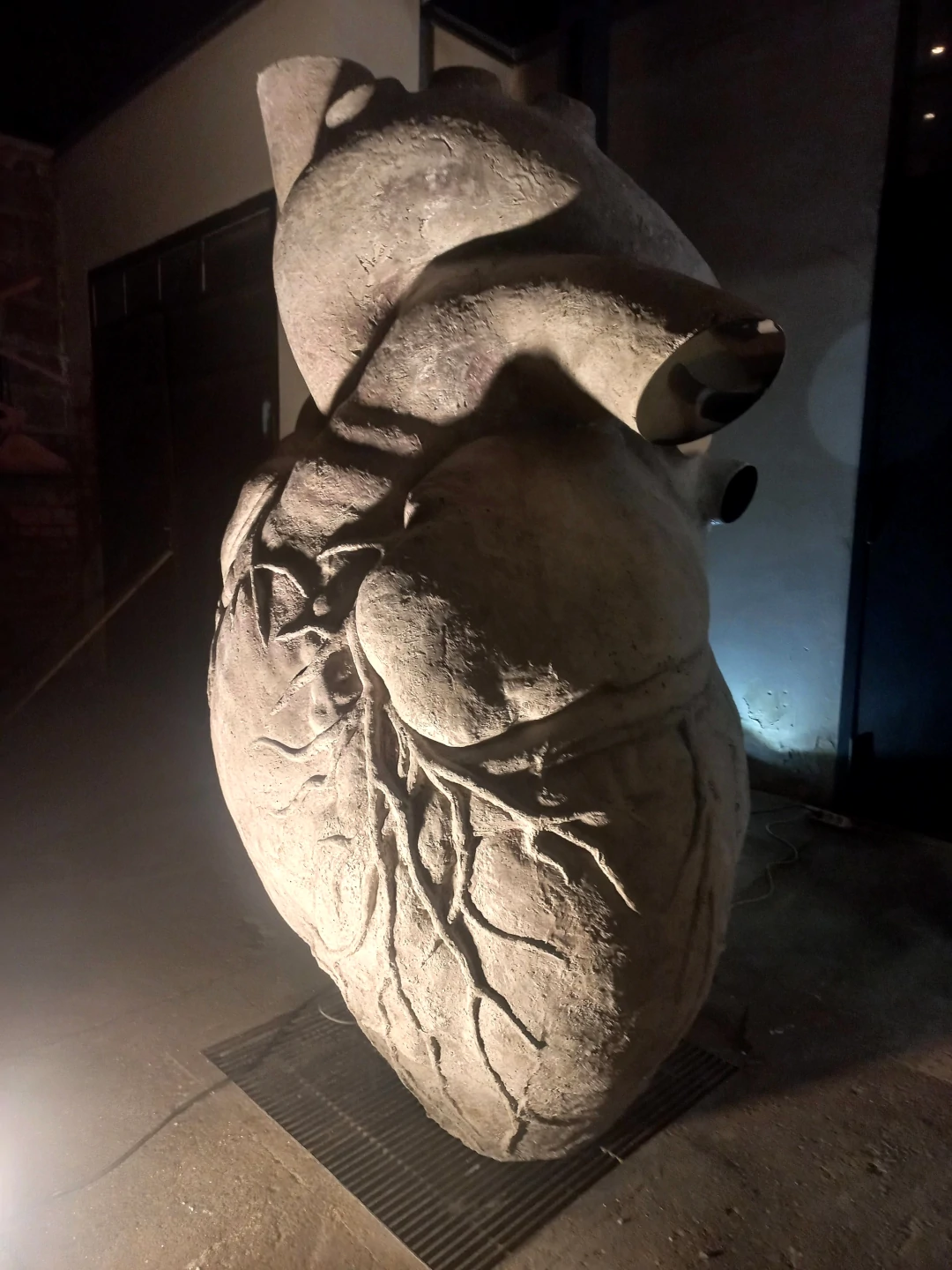

After a thorough maturation it was time to release the cast from the plaster. We carefully cut away the plaster. Thanks to the perfect separation and polished surface, it bounced off the model very well. We pressure-washed the model with water and we were done! One solitary perfectly seamless casting.

The author Veronika Durová added stainless steel "mirrors" to the heart on the imaginary cuts near the arteries and veins.

The heart was presented at the opening in Prague's PRÁM gallery on 22.2.2023 (link)

Veronika Durová (*1984 in Prague)

In her work, Veronika Durová develops a dialogue between matter and empty space. An example of this is the work with the substantive title - Dialogue (2012) - in which the physiognomy of the human body is sensitively transformed into a tension between the spoken and the perceived, the clear and the unclear, the tangible and the ungraspable. Four seated figures are reduced to mere legs and arms. And yet we feel that we are watching the whole figure, for in the concrete details, the stretching of the arms, the gesticulation, the crossing of the legs, the tension or relaxation of a given body part, we find a clear clue for our imagination. Because, Duro has applied the pauses of empty space so sensitively that they substitute for the missing mass, much as avant-garde composer John Cage once incorporated silence into his compositions as a full-fledged pendant of tone, the continuity of our "visual" reading is in no way disrupted. In short, Durova gives us the freedom to work freely with visual experience and to transform the unseen into the present through images stored in our minds. The choice of material - acrylic - which imitates the nobility of marble, but at the same time retains a great degree of fragility, plays an important role here, tuning our perception to the frequencies of silence and contemplative reflection on the questions of the reciprocity of the phenomena of the present and the absent, of spirit and matter.

Veronika Durová studied in the studio of Prof. Jan Hendrych in 2006-2012.

Commentaires